“THE RASMUSSEN”

Author: Glòria Serra Coch

By the 1970’s this book had already become a classic, a must-read among any group of architecture students.

However, nowadays, it seems to have been left aside on the endless pile of “very important books”, essential for an architecture student who has too many important things to do before reading them. Moreover, the book has somehow become a little bit out-dated, and is not considered as a trendy topic anymore, being seen more as a classic from another era.

Along this article, my intention is to give you a series of ten reasons why you should really stop doing this “very urgent stuff” in your architectural life and take a moment, or maybe more, to explore and even experience what “the Rasmussen” has to offer. This review has no intention of being a universal truth or even being objective. It is an opinion, a valid opinion I hope, but with a completely subjective scope.

REASON ONE: THE TITLE

This first point might seem an obvious one. It is said we shouldn’t judge a book by its cover, but we all end up doing it and, by its cover, I also mean the title, of course. Experiencing Architecture is an interesting title for a small and, seemingly simple book. Why choose experiencing architecture? Why not analysing, observing or living? These other verbs might have been used much more often when speaking about architecture. The answer can be found in a fragment of the writing.

“Understanding architecture, therefore, is not the same as being able to determine the style of a building by certain external features. It is not enough to see architecture; you must experience it. You must observe how it was designed for a special purpose and how it was attuned to the entire concept and rhythm of a specific era. You must dwell in the rooms, feel how they close about you, observe how you are naturally led from one to the other. You must be aware of the textural effects, discover why just those colours were used, how the choice depended on the orientation of rooms in relation to windows and sun.. You must experience the great difference acoustics make in your conception of space: the way sound acts in an enormous cathedral, with its echoes and long-toned reverberations, as compared to a small panelled room well-padded with hangings, rugs and cushions.”

The title is giving to the potential reader a sample of what the book has to offer. It is a clear contraposition of the chapter titles, the next thing one would probably look at, which seem to have a more formalist approach, and beware of my use of “seem to in the sentence. In this way, these first words are giving the reader the mood in which the book has been written and should be read. It is offering the first clues about a content that will deal more about perception than formalism or styles and therefore settles the beginning for what is coming next.

REASON TWO: BECAUSE THE AUTHOR IS NOT ONLY AN INTERESTING ARCHITECT OR CRITIC BUT HE ALSO KNOWS HOW TO WRITE.

Steen Eiler Rasmussen (1898-1990) wanted to be an architect since he was 9 years old but he ended becoming more a writer or a teacher. Nevertheless, he did work as an architect, addressing different scales and genres.

He was always interested in the issues of architecture, mostly the ones related with the cities and its inhabitants. In 1919, he won the competitions of two important urban plans: Hirtshals and Ringsted. However, possibly his most important contribution to architecture and urban planning was the Copenhague extension plan (1948) known as the plan of the fingers and with a main goal: to reduce diary city movements, a very contemporary conception of city problems.

However, as it has been stated before, he was more of a writer and a teacher than an architect and, in fact, a very good one. The book not only exposes interesting contents but also a very structured discourse. With plain language, understandable for everybody, he exposes the different ideas with a semi – free order. The observations made are classified following the themes of the chapters but also organized through a series of anecdotes and stories, connected between them through a discursive thread not always as strict as the main classification would suggest.

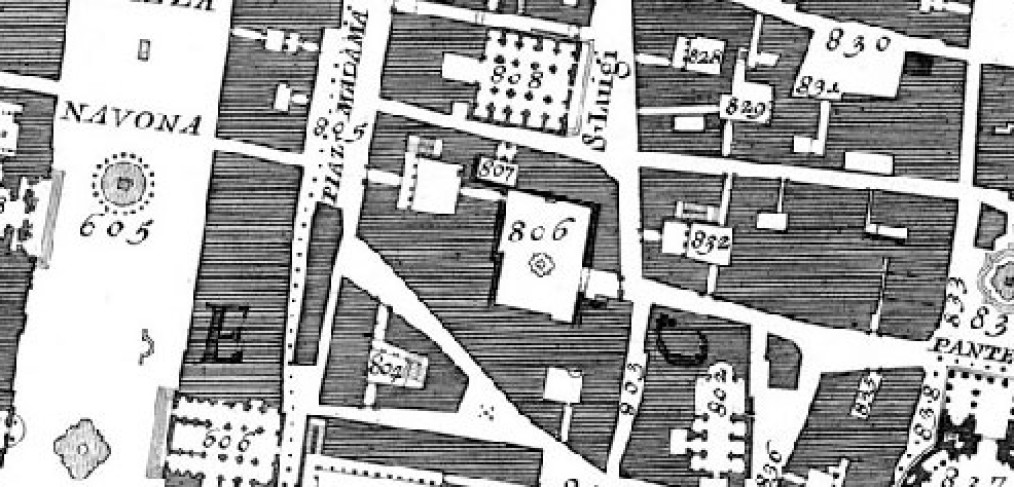

In the second chapter: Solids and Cavities, he starts reflecting on the viewing act of a personal subject, to after amplify it to the viewing and recognizing process in general. Without the reader even noticing, he manages to redirect the subject to the objects that have been given human characteristics. The transition is very smooth and logic, though it might seem that the thread has still nothing to do with the title of the chapter. However, by expanding the process of objects humanization to cities, he succeeds in referring to the observation process of figures in the space, through the analysis of the Nordlingen city, and, from there, he starts developing the theory of the mental “images” of objects that humans have.

This concept is the introduction to a figure that expresses the contraposition between the vacant and the full, the mass and the emptiness, the solid and the cavity. It is at this point that the reader finds himself in the core of the argument without even noticing how he has been taken there. From this point, a precise and logic development of the main idea follows. Starting with etymology and continuing with architectural examples, by the time that the chapter is finished the reader has completely apprehended this new concept and, more important, he is able to look at his surroundings and start analysing through this new layer.

REASON THREE: THE STRUCTURE

The book is structured in ten main chapters plus an introduction. Each chapter has a title referring to its content. This first statement might not seem very unusual but such clarity is not always the case in architecture publications.

I. Basic Observations

II. Solids and Cavities in Architecture

III. Contrasting Effects of Solids and Cavities

IV. Architecture Experienced as Colour Planes

V. Scale and Proportion

VI. Rhythm in Architecture

VII. Textural Effects

VIII. Daylight in Architecture

IX. Colour in Architecture

X. Hearing Architecture.

However, at second glance, the attentive study of the summary will start raising questions. If this is a book about experiencing architecture, which is exactly what the title points out, could we find in this ten items list the summary of all the factors involved in the process? Could we build a graphic and evaluate how our experiences have been regarding an architecture work by evaluating each factor one by one?

Obviously, this was not the intention of the publication. Even if it clearly states a classification through the chapter’s nomenclature, we ought to think about it as a possible list of points of view to consider, a list that could be amplified, changed, reviewed…etc. Probably, we could all find some aspects we would like to add because we consider them important enough in the experience of architecture.

Nevertheless, does this mean that the structure has no value? If it could be changed or modified then, why is there a structure at all? Why making the effort of creating an order, a list of fundamental concepts if this same order could evolve and adapt to new perspectives?

The order helps us think about reality, analyse it and research it. The classification in our mind is a way to address knowledge and be able to build theories and new perspectives from it. However, it is important to accept the mutability of classification as, when it has already given everything we can take from it, it is important to be able to move on to the next phase, and break all the pillars of the structure we have built.

Another aspect to take into account about the organization is the fact that, looking at the titles, it might seem that the book is developing a completely formal approach to architecture critique. It is important to realise that this is not the case. Experiencing architecture is creating reflections about phenomenology using formal bases to start on.

REASON FOUR: NOT TAKING THE STEREOTYPES FOR GRANTED

As a student, when you first step in the architecture school, you realize that there are at least a thousand things you should already know, many seemingly very important people you should at least have heard about and, obviously, you must have a clear idea of what is right or wrong, beautiful and ugly, correct and incorrect…

Nevertheless, when Steen Eiler Rasmussen starts writing about all these very well-known architects, these references made people; he describes them without any prejudice or preconception. The author does not take for granted that the reader must know every building he is talking about or every style he is describing and, in this way, every kind of person can follow the book without problems. At the same time, when the reader has a larger knowledge about the subject, Rasmussen is always able to add a new perspective that makes the traditional new again.

In this way, the reading becomes a placid and fluent activity for any kind of user, without feeling neglected for not having enough knowledge to follow the main ideas, but also keeping the interest and attention of the most cultivated readers by adding layers of interesting observations maybe noticed only by a few.

Moreover, it is also interesting to notice the tone the writer uses to refer to these famous architects. For him, they seem to be more like appreciated colleagues than the famous stars they might be seen as nowadays. Rasmussen does not make a difference between the ones that might be worldwide famous or others that have just an interesting architectural work. He does not seem to have prejudices of style or period when looking for the right example to illustrate a concept. Obviously, there can be found a larger amount of references from Denmark and surrounding areas than usual, but this only adds interest to someone with the intention of expanding his references catalogue.

All in all, the courteous and placid way of dealing with other architecture leading figures is appreciated. The lack of blind adoration or bitter criticism gives a truce to the tension-built relations usually found in architecture.

REASON FIVE: MAKING CONNECTIONS

When studying architecture, one discovers that architects do not tend to learn subjects very deeply and, although numerous different fields are introduced during the studies, not many are developed in depth.

This situation is a result of the character of the discipline, built by the superposition of knowledge from very different areas. For an architect, it is not only important to know about physics, but also geometry, history, sociology, aesthetics, philosophy, materials… Many centuries ago, when describing the figure of an architect, Vitruvius already stated this fact by presenting such a long list of the qualities and knowledge an architect might need that it seemed a person of these abilities could never be found. However, as it has been introduced before, the price to pay to be able to deal with such different areas of knowledge is usually the reduced expertise achieved in each of them.

On the other hand, to be able to make a use of all these vast knowledge placed in different fields, it is important to develop the ability of making connections. The idea of a project should be the result of a layering process built by all the different factors coming from completely diverse fields and directions. Therefore, an architect should be able to see this bigger picture, establish the needed relations and, in this way, becoming capable of coordinating all the people participating in the process of creating architecture.

Rasmussen is dealing with the connection process all the time throughout the book. By picking up a concept he is able to relate it with elements of different periods, styles and subjects. A clear example is found in the chapter where he develops the concept of “planes of colour”. He is able to write about architecture of Venice, lightness versus weight in architecture, Le Corbusier and Japanese traditional architecture without losing the thread that connects all the elements of the discussion. In fact, a very interesting game could be played using the book. If several references were given to the reader, would he be able to know which concept is the author writing about?

In any case, the ability of making connections is fundamental for an architect. Therefore, it should be appreciated that a writer exploits it in his book in such a mastered way, by building the discussion through a structure of connections.

REASON SIX: BECAUSE YOU UNDERSTAND WHAT HE WRITES AND IT SEEMS LIKE HE DOES TOO.

“But if it can be understood by a fourteen-year-old then certainly it will be understood by those who are older. Furthermore, there is also some hope that the author himself has understood what he has written – which the reader is by no means always convinced of when reading books on art.”

When reading Experiencing Architecture, one has the pleasant sensation of being offered something specially chosen for him. The feeling is reinforced by several references to the reader through the text, causing a sensation of having established a dialog with a nice professor from another era.

In the end, the main reason that induces this sensation of attention is probably because the author is writing thinking about the reader with the aim of educating him. Therefore, he writes for the reader and not for himself.

However, this simplicity in its communication has the risk of inducing to take the book as a basic one. After taking a look at it, it is easy to believe that one is above such simple and obvious ideas and dismiss further investigation. However, the writing is built in several layers in the structure of the writing, which makes it comprehensible for everyone at their own level.

All in all, if someone reads it with attention and an open mind and still has the feeling of being above it, he is probably missing the real significance of it.

‘’The language in ‘Experiencing Architecture’ is so lucid and clear that every layman and beginner will be able to understand and to enjoy it’’.

Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism.

REASON SEVEN: BECAUSE HE JUSTIFIES WHAT EVERYBODY SAYS IT IS IMPOSSIBLE TO JUSTIFY

At the architecture school, there are some things you are taught in a rather non reasonable way. Some projects are amazing just because they are, and some architecture is ugly and despicable just because… if you don’t see it, that is your problem.

Luckily, there are also these kinds of professors that explain all the insights of an architecture work and the reasons why some aspects are very interesting or good, and some others are clearly a mistake. These reasons, however, are always closely linked with time periods, social issues, fashions, temporary interests, contraposition with the existing… everything very flexible, subjective and changeable.

In the end, the general sensation is that a smoke of educated opinion is the decisive last push of every decision in the frame of architecture critique. At the architecture school level, it is easily accepted that projects and designs are evaluated in a rather random system, where the opinions of the teacher, what he likes and he does not, or the marketing of the idea, can be the main part of the grade.

However, sometimes, it is possible to find someone that explains you clearly why do you have this discomforted sensation when you look at that specific staircase. One of these people is Steen Eiler Rasmussen.

We can clearly see this intention in a passage of the beginning of the book. In the chapter he calls Basic Observations, he starts a dissertation about the soft and the hard and he gives several examples to illustrate it. In this context, a masterful explanation is given when he writes about the brick pavement of a part of Copenhague. The author explains in a very clear way, why is it irritating compared with the pleasant one of The Hague, also made of brick.

“In the Netherlands bricks are used in streets and roads, and a pleasant and cared surface is achieved. However, when this material is used as a support of the granite pillars – as it is the case in the Stormgadre, in Copenhague – the effect is far of being nice. Not only the brick splinters but also one has the unpleasant sensation that the pillars are sinking in a softer material. “

REASON EIGHT: BECAUSE HE HAS A GOAL

‘’Art should not be explained, it should be experienced’’

Many times, when reading a book, one wonders why the writer decided that this specific subject would be the theme of his publication. At the same time, it is usually also a mystery if he had any goal that motivated him to write a book at all. In general, these secret reasons tend to be explained at the preface by the same author. Many times, a personal experience seems to be the trigger of the original idea. In other cases, the book is a compilation of a number of items which, after a selection and revision, are assembled to build a whole. This case might be conferences, lectures, articles or even the results of investigations or exercises with students.

However, very often, even if a reason is given explaining why the author wrote the book there is a lack of a goal that transcends personal situations or feelings. Rasmussen, while writing Experiencing Architecture, not only has a clear goal, but also states it in a very direct way. Moreover, he also explains for whom the book is written and why this affects its structure.

’My object in all modesty is to endeavour to explain the instrument of architecture, to show what a great range it has and thereby awaken the senses to its music’’.

REASON NINE: BECAUSE HE KNOWS HOW TO EXPLAIN CONCEPT BOTH WAYS, FROM THEORETICAL POINT OF VIEW AND THROUGH ANECDOTES

“They were pupils from a nearby school. They had a recess and employed the time playing a very special kind of ball game on the board terrace at the top of the stairs. When the ball was out, it was most decidedly out, bouncing down all the steps and rolling several hundred feet further on with an eager boy rushing after it, in and out among motor cars and Vespas down near the great obelisk.”

When explaining the concepts of the book, the author is always transmitting them in two ways: Firstly, by giving a brief and clear statement about the thesis exposed and, afterwards, illustrating the concept with a clear example. The order can vary sometimes depending on the requirements of the context or the need of creating an effect in the writing, however, the dual structure can always be found.

These examples or anecdotes usually create a dialogue between the life and architecture, the form and the functions, not speaking about well-known buildings from a formal point of view but using any built environment and linking it with its use.

“It is not my intention to try to teach people what is correct, beautiful… It is to show which instruments the architect plays to make his music appreciated. However, it is very difficult to hide tastes; it is not enough to explain physical aspects. It is necessary to play an instrument to hear its possibilities.”

Therefore, with these illustrations of reality related with his theories he achieves a thorough understanding by the user by “playing the instrument to hear its possibilities”.

REASON TEN: BECAUSE HE CONNECTS ARCHITECTURE WITH LIFE.

While reading the titles of the chapters and looking at the subjects Rasmussen seems to deal with, it might come to your mind that the book is a structured dissertation about formalism in architecture. However, it could not be more opposite to this idea. When the author writes about architecture and reflects on it, he always makes very clear its relation with the use and life, becoming the frame of every human activity.

“Architecture is a very special functional art; it confines space so we can dwell in it, creates the framework around our lives. In other words, the difference between sculpture and architecture is not that the former is concerned with more organic forms, the latter with more abstract. Even the most abstract piece of sculpture, limited to purely geometric shapes, does not become architecture. It lacks a decisive factor: utility.”

Although the word utility might currently have negative connotation due to its close and confusing relation with functionalism, it is necessary to realise that, in this case, it is making a very contemporary point. By comparing architecture with other plastic arts, the writer states the importance of taking into account its use by humans. In this way, the idea dissociates itself of the formalism most architects have adopted to work with the projects and introduces the fact that, in the origin and at the end, architecture is made by humans for humans, and it is nothing more than the creation of the place where our life is going to develop.

“The architect is a sort of theatrical producer, the man who plans the setting for our lives. Innumerable circumstances are dependent on the way he arranges this setting for us.”

This idea is reinforcing the fact that the important part of architecture is not the shell but the life we can find within. In this way, the focus is set on the motion rather than in the static part and the architect is introduced as the “theatrical producer” of this action. This perspective is offering two interesting points: Firstly, the fact that the writer places the architect in a more humble situation than many other reflections about architecture. He is not the director of the play or the leading actor and, usually, nobody remembers the name of the theatrical producer. Secondly, the idea that architecture is something that is created by a group, and not an individual, and, therefore, the position of the architect is nothing more than the coordinator of the team. This notion might seem very normal today because it has been trending topic lately; every discussion in architecture ambiances has something to do with it. However, the idea of the head architect and the half-god creator still persists.

“Another great difficulty is that the architect’s work is intended to live on into a distant future. He sets the stage or a long, slow moving performance which must be adaptable enough to accommodate unforeseen improvisations.”

Last, but not least, is the contribution made in this paragraph. With simplicity and in a way that could easily go unnoticed by the reader, Rasmussen is introducing the idea of time in architecture. Therefore, the architecture he describes as a stage is not a static solution but an “always in motion” frame that needs to be flexible to be able to incorporate the “improvisations” the life of the space will live.

As the anonymous author of “the Sleep of Rigour” states, “This is different from the idea of trying to provide a neutral or empty frame that users complete, fill in, or transform. That is to say, there is something lazy, and indicative of a bucking of responsibility, in the way some architects put the onus on the ‘making’ of architecture on the users, by providing solutions that are mere shells or frameworks”

TO CONCLUDE, it would be interesting to give an insight of the reason why I have been referring to the book as “the Rasmussen” through the whole article and why have I given this title to my post. The main reason is a very plain one. Most of the people in the field tend to call the publication like that, and not by its official name.

This is a phenomenon very common in architecture books and, as I have observed, other kind of essays and scientific publications. We can think of several examples we would be able to name the author of the book easily but not the title that fast: The Vitruvius, the Zevi, The Frampton, the Benevolo…

The reasons for this circumstance are probably diverse. It could be laziness to use a long sentence instead of a single word, it could be the egocentrism always linked with architecture, the fact that many books have similar titles… However, I would like to focus on one possible explanation: The fact that, by using the name of the author, the attention is placed on the point of view instead of the object. It is not as important the subject that is being discussed as the way it is being discussed.

REFERENCES

Experiencing Architecture, Steen Eiler Rasmussen. Editorial Reverté, Barcelona 2007

Architectural Principles, North Coast Architecture Center, AIA Redwood Empire Chapter.

http://www.northcoastarchitecturecenter.org/education.php

Steen Eiler Rasmussen: Experiencing Architecture. The Sleep of Rigour. August 2012.

Steen Eiler Rasmussen: Experiencing Architecture

Book Review of Experiencing Architecture. Alannah-Rose Ogrady K. ARJOGK. March 2014.