Montagist Architecture

Author: Federica Sofia Zambe

Paul Mosley

Project

American social utopian traditions show that architecture is fundamentally driven by ideology. Architecture was the means by which Shakers and Hippies alike directly expressed their ethos and ritualized their lifestyle. Many of these theocratic and socialist communities did not last beyond two or three generations, (only three active Shakers remain in the world) and their planning visions were often rhetorical.

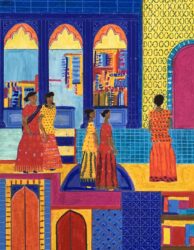

In this project, the Exploding Edenic Inevitable, the core design approach is to remake, appropriate, and hybridize references from worlds that are alien to one another. Stemming from the distinction between content and representation, this work synthesizes the ideals of utopianism and appropriation into a proposal for a building in Chicago with three parts: public space, a commercial plinth, and a tower of housing.

Within the tower, the domestic interior synthesizes the uncanny commonalities between the architecture of Mies van der Rohe and the Shakers (Mies’s “God is in the details” and the Shaker’s aesthetics of incarnation). These principles are accomplished above all via the construction of images, which surpass the plat distinction between virtual and real by devouring references in both pictorial form and deep representation. The following paragraphs contextualize the collage After Gericault within the pictorial tradition of Leon Battista Alberti’s concept of istoria, and positions it within the concept of montage, which is a fundamental category of collagist work in contemporary architecture.

.Collage, more than any other form of representation in architecture, offers the opportunity to steal history, synthesize fragments, and transform precedents. Collage is a specific idea, it measures the work of others through appropriation, rather than merely repeating it. The art-historical principle of istoria, coined by Alberti, helps to elucidate the representational value of After Gericault. This investigation decontextualizes the principle of istoria by shifting its pictorial meaning into the domain of architectural discourse.

Central to an understanding of istoria is a concern for the space between the beholder and beholden. Unlike the cubist or postmodern artifacts of collage, which are often compositional, today’s digital collages in architecture are synthetic and graphic. After Gericault privileges both real and imagined content; it conflates pictorial images with architectural objects, and engages the collagist principle of montage as a formalist technique.

Alberti coined the term istoria to describe the relationship of subjects and objects in Della pittura (1435), the first modern treatise on a theory of painting. He began writing Della pittura in response to the rise of Humanist pictorial art in Florence after his return to Rome from exile in 1428. In using the term istoria, Alberti analyzed and described the very nature of painting and the means of mathematically controlling it through perspective, composition, and color. He writes, “The greatest work of the painter is not a colossus, but an istoria,” privileging art’s meaning and theatricality, instead of its size. In premodern paintings, theatricality is often active in order to entertain the beholder, but in an istoria, theatricality guides and narrates the viewers gaze within the representational space of the painting.

Alberti’s use of a “commentator” in an istoria establishes a narrative link between the painting and observer, as well as an emotional link. The commentator, he writes, “beckons us to see, warns us with flashing eyes, or directs our gaze to something marvelous.” In an istoria, the experience of pictorial illusion in virtual space is indistinguishable from the experience of what the image depicts in actual space. After Gericault appropriates the concept of istoria by redefining and transforming its meaning for architectural representation.

After Gericault incorporates a fragment of Theodore Gericault’s first major work, The Raft of the Medusa (1818-1819), depicting a group of survivors of the 1816 shipwreck of the French naval ship Meduse. In this collage, architecture is devoid of strong content—it focuses on the formal dynamics of perspective composition through the technique of montage. The effect of depth between the active foreground and the background is useful for illustrating the actual and representational space between viewer and picture.

In After Gericault, the shipwrecked survivors act as commentators, directing one’s gaze outwards toward the horizon through an opening between two walls. The perspective is focused on a point framed by three lines. The first line being the left vertical edge of the ghosted background building. The second being the diagonal created by the two rags being held by the right-most survivors. And the third is perpendicular to this diagonal created by the directionality of the group’s collective posture. This perpendicular diagonal is most clearly indicated by the linearity of the centermost survivor’s arms and the direction of his gaze. Within the flatness of the picture plane, the survivors act as ‘commentators’ by mediating between the actual space of optical viewers and the representational space of pictorial theatricality.

.Through a unified perspectival viewpoint, the technique of montage creates the illusion that two unlike things belong in the same representational space. With collagist work in architecture, (the “non-official movement” Fala Atelier refers to) illusionistic representation collapses the difference between unlike elements, and synthesizes form and precedents into a coherent, autonomous image.

Interview

Who influences you graphically?

I am influenced by many graphic references. I am for an ethic of graphic expediency, and against abstract heroism. Many offices (mostly European) embody this kind of ethic today: Sam Jacob, Alexander Eisenschmidt, Dogma, Office KGDVS, 51N4E, Fala Atelier, Point Supreme, Monadnock, 2A+P/A, OMMX, Valter Scelsi, Baukuh, Yellowoffice, Design With Company, Johnston Marklee, NP2F, Carmelo Baglivo, Productora, and Wai Architecture Think Tank, among others (not to mention Diploma 14 at the AA). The students of these offices and teachers are equal influences. Do these offices exist on the same plane? By no means. They’re all different ages, and have different histories—but they each share what Fala referred to as that “unofficial movement,” a movement that KooZA/rch often represents. I see it less as a “movement” than as an emerging meta-project in architecture—one that is fully invested in representation.

I believe that collage heralds the end of style, which is why this “movement” remains unofficial and nameless. Its purpose is to facilitate a conceptually motivated graphic sensibility. Therefore, any attempt to give it a name destroys it.

Apart from these architects, fine art in general, especially painting, is my most important reference. Painters like Giorgio Morandi, John Register, Luc Tuymans, David Hockney, Edward Hopper, Georges Seurat, Vilhelm Hammershoi, Henri Rousseau, and Edouard Manet come to mind. I look for framing and composition, colour, atmosphere, positionality, brightness, dullness, distortion, literalness, and qualities of light.

You talk about collage as creating the illusion of two things belonging in the same context, nonetheless the mere placing of them in such proximity for you defies the term illusion and makes it real. As such what do the terms in and out of context mean for you?

The contrast between depicted subjects and their context was present in early Impressionism. There, the blurry ethereality of context and surroundings reflected the spectacle of traffic and changing atmospheres that animated the market and industry at that time. Depicted subjects owed their income and freedom to this animate context, but were represented as separate from it. Today, our historical circumstances and present condition are different—the graphic distinction between the depiction of individuals and their context is an act of resistance.

A movement away from abstract heroism towards graphic expediency is not merely a reaction to the complacency and platitudes of inflated online magazines. It is representative of the cultural situation we are currently in. This situation is a dissolution of autonomy within digital media and commercial capitalism. The absolute nature of depicted subjects resists this dissolution, attempting to recover the autonomy not of heroic form, but the autonomy of the individual’s absolute form of life.

Can the drawing and representation of architecture be more ‘architectural’ than architecture itself?

My argument is that images of buildings are no less real than buildings. The distance between the image of a thing and the actual thing—between architecture and its reflection—is very thin. It’s not a matter of placing one above or below the other, but giving them equal weight. Some would argue that this raises the representation of architecture to the status of art. I argue that this raises the drawing to the status of architecture in its real (not virtual) form.

It’s possible to have a productive exchange between the disciplines of art and architecture without confusing or equating the two. I attempt to be productive in this way.

To what extent do you agree with the idea that an architecture even at the level of a building is always representation?

Absolutely, I agree. In the spirit of transparency, the phrasing of your question is exactly the same as what Sam Jacob says in his essay “Drawing as Project: Post Digital Representation in Architecture” (published in FM Journal VII: Collage). So to borrow his argument, which I agree with, architectural representation and its reality exist at the same time. Architecture’s “representational qualities are not different from its real qualities as a building but are always simultaneous.” This is also a similar argument that P.V. Aureli makes in his essay “Manet: Images for a World Without People” (published in Scapegoat 03) where he says that both the representation of architecture and architecture are equally (but not equal) objects.

What dictated the variety of image styles through which you represented your proposal?

The variety came with my desire to experiment. What can an exterior section perspective do that an interior perspective cannot?

What happens if the context is drawn with cross hatching? How might color, texture, and orientation provide a greater perception of depth or flatness?

The answers to these questions are guided by references: How does Piranesi focus perspectival views? How does Anthony Ames’s paintings—although perspectival—create the perception of flatness?

What influences your choice of paintings to decompose and appropriate through your perspective views?

Paintings are often used in architectural drawings as mere fodder for entourage. I try to use architecture and the problem of painting as one of perspectival composition, perception of color, and control of depth—rather than fetishizing the effect of brush strokes. In my work, this is most apparent with After Gericault and Somewhere between Mies and Quakers.

The Exploding Edenic Inevitable

The Exploding Edenic Inevitable

The Exploding Edenic Inevitable, Axonometric

The Exploding Edenic Inevitable, Courtyard Section

New Harmony in a State of Ruin after Piranesi

Transfiguration of Mies’s Country House in Brick

Transfiguration of Mies’s Country House in Brick

Transfiguration of Mies’s Country House in Brick